New philanthropy in the Dominican Republic: from foundation towards profit generation

This Blog Post is contributed by Alejandro Caravaca, D. Brent Edwards Jr. and Mauro C. Moschetti as part of the NORRAG Blog Series on Philanthropy in Education (PiE) which aims to foster dialogue between key stakeholders on critical issues relating to the global and regional role of Philanthropy in Education. In this Blog Post, the authors shed light on the role of influential philanthropic actor Inicia Educación in the context of network governance in the Dominican Republic.

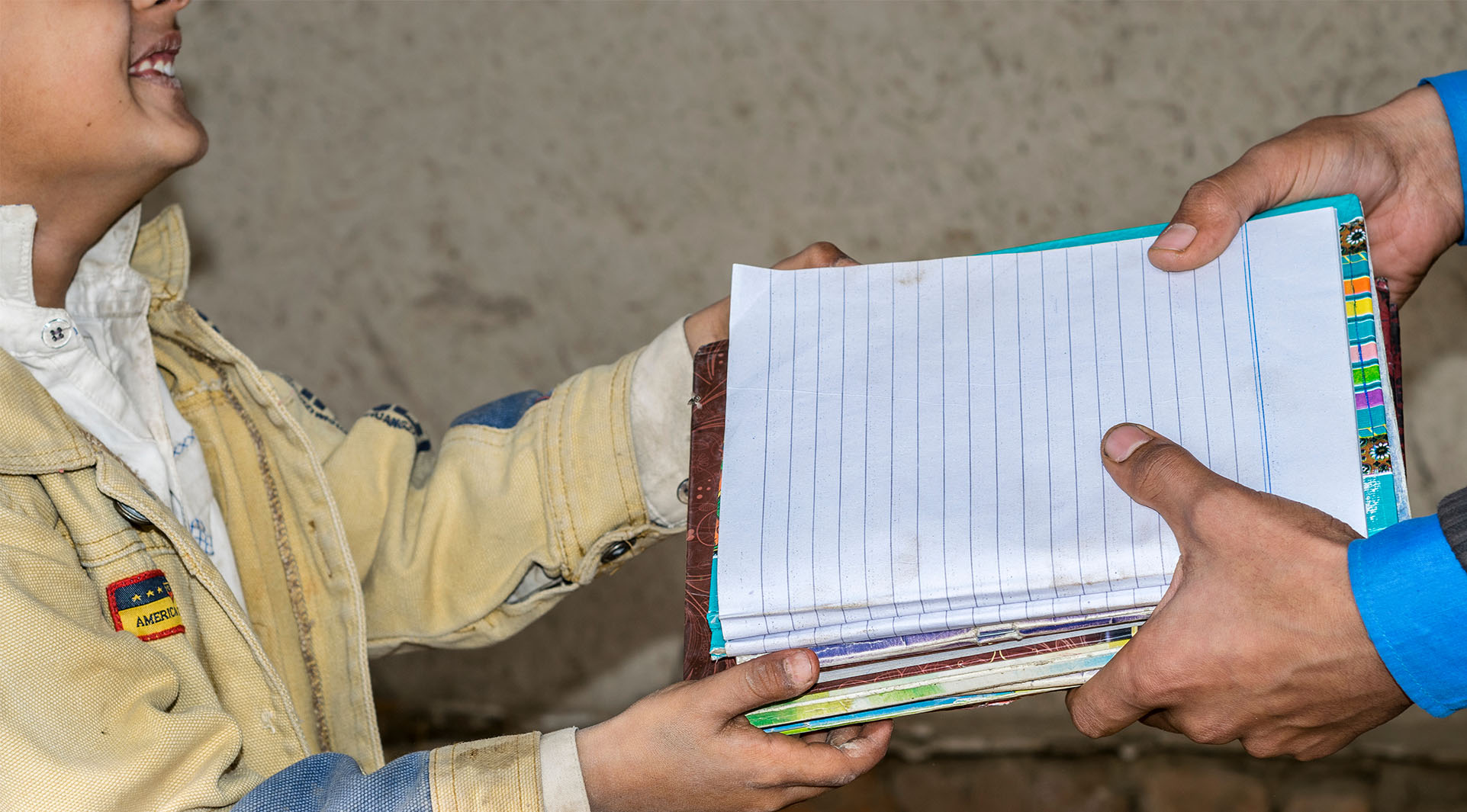

Traditionally, philanthropic organizations in education have mostly dedicated themselves to the donation of materials—e.g., textbooks, backpacks—to schools or families, building school infrastructure, or even funding certain education projects. Nevertheless, in recent years, the orientation of philanthropic actors is shifting towards what some call “new philanthropy”, “venture philanthropy”, or “philanthro-capitalism”.[1] As Sarah Reckhow and Jeffrey Snyder explain, beyond the donation of resources, philanthropic actors are increasingly engaging in policymaking by “supporting groups involved in policy advocacy, funding organizations that promote competition with public sector institutions, and providing convergent funds to key groups advancing favored policy priorities”.[2] Additionally, ‘new’ philanthropists depart from a more business-oriented paradigm, which has blurred the lines between charity and investment.[3] In some cases, they seek to generate profits for themselves, for their funding organizations, or for other private sector actors who can benefit from their involvement in the education sector.[4]

With the above in mind, in a recent study [5] we were able to shed light on the role of an influential philanthropic actor in the context of network governance in the Dominican Republic. The name of this philanthropic actor (discussed further in what follows) is Inicia Educación. What stands out about the case of Dominican Republic, among other things, is that, since 2012, the budget for education has been increased dramatically, following civil society mobilization. And what stands out about Inicia Educación (as well as other non-State actors) is that it perceived not only the opportunity to involve itself in agenda-setting and to influence decisions about how increased funding should be invested, but that it also saw an opportunity to generate profits for itself.

The case of Inicia Educación

Although Inicia Educación is a relatively young philanthropic organization, having been founded in 2010, it is only the most recent manifestation of the philanthropic history of the Vicini Group. The Vicini Group, whose roots date to the 1860s, is controlled by the wealthiest family in the Dominican Republic. It has subsidiaries in the banking, financial services, and agro-industrial sectors. Up until 2010, the Vicini Group engaged in traditional philanthropy, where a part of its profits would be converted into donations for school materials and school construction, in addition to making contributions to the health sector, among others. However, in 2010, its philanthropic focus changed both its area of interest—now exclusively education—as well as its modus operandi—from traditional to new philanthropy. The moment that most symbolizes such a conversion occurred in 2016, when the name was changed from Fundación Inicia to Inicia Educación. By dropping the label of foundation and projecting an image of itself as an investment fund, the philanthropy left behind the kind of traditional assistance for which it was historically well-known and shifted instead towards the adoption of a business mindset and the use of business language, e.g., talking about ‘investment’, ‘measurement’, ‘impact’, etc.

Actors across the Dominican education system acknowledge the role of Inicia Educación not only in designing and executing its own projects but also in formulating government policy. Several actors characterize Inicia Educación as a great ally of the Ministry, and one which has had significant influence on shaping public education policy in recent years. As the government itself admits, Inicia Educación “manages projects, executes and finances concrete, innovative projects. … They offer support to the Ministry of Education in terms of the budget on issues that have been agreed upon” (Government representative). In this regard, Inicia Educación has become a trusted actor due to its technocratic working style and its ability to mobilize expertise and resources, which has served as an entry point into the Ministry of Education.

However, it is also the case that recent developments reveal the willingness of this organization to use its privileged position to generate profits for itself and its parent entity. In other words, Inicia Educación now seeks to use its leverage both to shape policy and also to generate revenue—both within the Dominican Republic and beyond. Interestingly, until 2016, Inicia Educación operated exclusively with the funding that it received from the Vicini Group. However, in that year, along with the name change, it began to pursue a new strategy: to generate its own income, taking advantage of the knowledge and skills that it had developed, through a new entity called “512”. 512 functions as a private, for-profit consulting firm that is legally independent from Inicia Educación but which is completely linked to it in practical terms. As a non-profit entity, Inicia Educación can continue to work with the Ministry of Education, collaborating free of charge and providing donations, while, at the same time, generating revenue through other activities for which it has been contracted through 512. Notably, 512’s profit-generating mission reflects the capitalist orientation of the organizations that have given rise to philanthropies like Inicia Educación. Moreover, although 512 is, in economic terms, the principal and Inicia Educación is the agent, in practice, it is the other way around, with the implication being that a philanthropy is directing, if not formally controlling, a for-profit entity. And, ultimately, although there exists the (stated) intention of reinvesting profits in further education projects, there is nothing to stop project revenue from being treated as profit which is either retained by 512 or repatriated to the Vicini Group.

Understanding and counteracting perverse effects of new philanthropy

Having briefly explored the role and the shift from traditional to new philanthropy of Inicia Educación, the task going forward is, on one hand, to support non-governmental organizations and civil society mobilizations in order to pressure the State and to provide a counterweight to the advice and influence of new philanthropy. On the other hand, going forward it is important to examine and explain how political-economic considerations have facilitated both the emergence and strengthening of new philanthropic organizations as well as the weak position of States vis-à-vis such actors.

In the context of the Dominican Republic, this would mean extending the insights presented here and connecting them with an analysis of the relationship of forces that have surrounded the State and that have been settled through it historically.[6] Doing so may well reveal that the Dominican State has never had the chance to develop its resources and capacities to the extent that would be required for it to more fully avoid or to challenge the contributions made by network governance and new philanthropy in the context of globalization. In recent years, some of these actors have sought to use their technical savvy to influence how the states invest their education budgets. At the same time, such an analysis would likely highlight the way that the global economy and domestic politics have consistently rewarded those who control exports (e.g., those from which the Vicini family has benefitted, such as sugar and coffee) while at the same time incentivizing those at the helm of the State to use their powers in self-serving and clientelistic ways, rather than building the power and independence of the State apparatus. These insights, in turn, can then feedback into the strategies for advocacy and the pursuit of alternatives to the status quo.

Alejandro Caravaca is a PhD Candidate in Education at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain.

D. Brent Edwards Jr. is an Associate Professor of Theory and Methodology in the Study of Education at the University of Hawaii, USA.

Mauro C. Moschetti is an Assistant Professor of Comparative and International Education at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain.

[1] See, for instance, Avelar, M., & Ball, S. J. (2019). Mapping new philanthropy and the heterarchical state: The Mobilization for the National Learning Standards in Brazil. International Journal of Educational Development, 64, 65-73; Saltman, K. J. (2010). The gift of education. Public education and venture philanthropy. Palgrave-MacMillan; Baltodano, M. P. (2017). The power brokers of neoliberalism: Philanthrocapitalists and public education. Policy Futures in Education, 15(2), 141-156.

[2] Reckhow, S., & Snyder, J. W. (2014). The expanding role of philanthropy in education politics. Educational Researcher, 43(4), 186–195.

[3] See, Terway, A. (2019). Introduction to Philanthropy in Education: Diverse Perspectives and Global Trends. In N. Y. Ridge & A. Terway (Eds.), Philanthropy in Education: Diverse Perspectives and Global Trends (pp. 1–14). Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

[4] For a thorough and updated account of this multidimensional phenomenon, see, Patil, L. & Avelar, M. (2020) (Eds.) New Philanthropy and the Disruption of Global Education. Norrag Special Issue 04. NORRAG. https://resources.norrag.org/resource/view/592/343

[5] The results of this study can be found in: Caravaca, A., Moschetti, M. C., & Edwards Jr., D. B. (2021). Privatización de la política educativa y gobernanza en red en la República Dominicana. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 29(128), 1-19; and in: Edwards Jr., D. B., Caravaca, A., & C. Moschetti, M. (2021). Network governance and new philanthropy in Latin America and the Caribbean: reconfiguration of the State. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 42(8), 1210-1226.

[6] In line with, for instance, Bob Jessop’s work— Jessop, B. (2016). The State: Past, Present, and Future. Polity.